This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure policy.

Back in 2012, Nike introduced Flyknit — an innovation that would dramatically change the aesthetic value of their footwear as well as the way it was produced. Shortly after, as in months after and also in 2012, adidas would unveil Primeknit — a nearly identical innovation that would also have added value to their brand in footwear in regards to aesthetics, performance and manufacturing.

To no surprise, Nike filed a temporary injunction that would halt adidas from not only selling Primeknit shoes, but also making them, claiming it was a copy of Flyknit.

To some surprise, Nike filed the original patent for Flyknit in 2004. Translation? When Nike was putting out LeBron’s rookie season shoe, the Air Zoom Generation, they were already readying the world for the LeBron 15.

*Explosion*

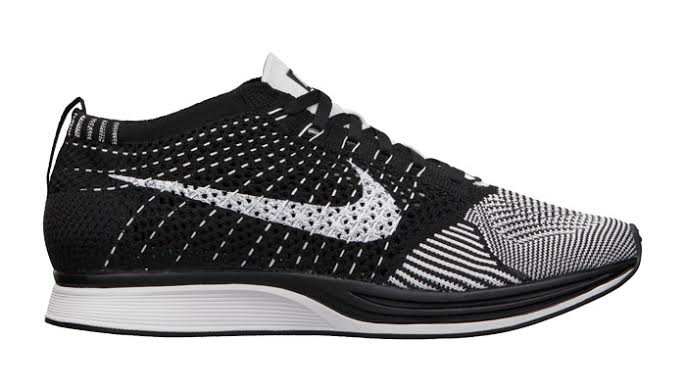

As the tale of the tape — or thread — would have it, Nike would have major success in 2012 with the likes of the Flyknit Racer and Flyknit Trainer. While all this was going on, adidas would essentially have to wait despite being a few months late to the party.

Why? In September of 2012, the District Court in Nuremberg, Germany would grant Nike’s application for interim injunction for patent infringement by adidas on the Primeknit sneaker. Due to said injunction, adidas was ordered to stop the manufacturing and distribution of Primeknit in Germany, where the brand is based.

In 2013, Flyknit flourished on models like the Lunar Chukka and has ever since, with the tech amassing “over $1 billion in sales” since its introduction in 2012, all the way up until time of publish as Portland Business Journal — the original source of this story — tells it.

All the while, back in 2012 and 2013, Primeknit continued to have trouble finding its footing. For the majority of 2013 and 2014, Primeknit technology was mostly visible and mostly available only outside of the US, with overseas drops at UK retailers resulting in stateside press. Primeknit models would see US availability and visibility most notably nearly two years after its 2012 unveiling, with the December 2014 drop of the adidas adiZero Primeknit Boost LTD.

The initial read on Primeknit by the mainstream was that it was a bite on Flyknit — possible in regards to aesthetic and manufacturing, but also improbable in regards to how long it takes to develop and turn out a product. (You’d have to be a true Big Baller to turn out a shoe or tech within months of seeing another brand do it.) The lawsuit hurt sales, due to lack of availability in Nike’s homeland of the US, but also perhaps created intrigue around it just the same.

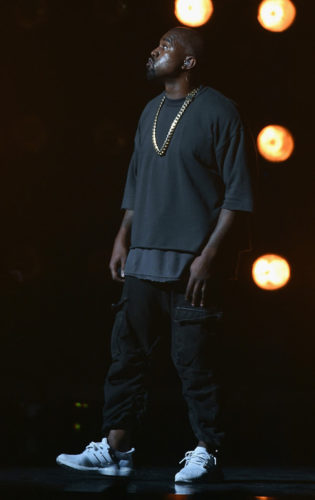

Buzz or barricade, this would all culminate with perfect timing in 2015, as adidas would release the very pivotal Ultra Boost. While the model would be championed early on as a performance running shoe, it would catch fire in the lifestyle space thanks to consistent wearings from Kanye West. It should be noted that while previously under contract with the Swoosh in 2012, Kanye’s surprise wear of the Flyknit Trainer with jeans — far from a track or treadmill — had the same effect on sales and interest for Flyknit, as far as the sneaker culture and resale market are concerned.

So, where are we in 2017? Both technologies matter and matter more than leather, both from an aesthetic marketing standpoint and surely in regards to manufacturing. Performance wise, both brands have even seen triumphs like the Hyperdunk 2017 Elite and the continued success on the fourth iteration of the Ultra Boost in basketball and running, respectively.

Despite success from both — or more likely because of it — the 2012 case is back in courts, as yesterday adidas filed an appeal with the U.S. Federal Court of Appeals. The brand is contesting an October 19, 2017 ruling by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board to uphold Nike’s patent for knitted upper technology, that was initially made in 2004 and brought to trial in 2012. Essentially, Nike’s patent granted them full ownership over making knit shoes and adidas of course doesn’t want that.

So, how are both sides where they are? As Portland Business Journal smartly pointed out in 2016, Nike is really, really good at filing patents — they recorded a record 687 new patents that year — essentially owning innovation and designs, both literally and figuratively. It’s easy to see why they’ve crushed for so long and continue to do so.

However, adidas is making the case that Nike’s 2004 patent that provided them ownership of the invention to make a knit shoe, both as tube shaped or attached to a sole — which also saves them time, money and waste in manufacturing — is no longer a new idea and essentially never was.

In the appeal, adidas claims that said construction is unpatentable, according to Title 35, Section 103 of U.S. patent law, which states that a patent can’t be claimed for an idea that would be obvious or effective before the filing date for anyone with experience in said industry. This is obviously arguable for Nike, as they were essentially eight years ahead of themselves on the idea and about a decade ahead of the industry in regards to knit footwear. However, there is a catch.

Eloquently put by Portland Biz Journal, “a person with at least a few years of experience in the footwear industry would have understood that the knitting technology was an option for creating footwear before Nike filed the patent,” despite said sneaker market trends. This argument has grounds on the fact that both stockings and panty hose essentially used the same manufacturing methods in a similar function/industry, seemingly forever. That manufacturing tech had never been transferred to sneakers though.

As alluded, since Flyknit and Primeknit hit in 2012, everyone in sneakers from Sketchers to Balenciaga has ran with knit footwear and seen great success. So, will Nike eventually re-own this space (though everyone is still clearly putting out similar product, despite the patent) and will other brands be forced to back out? It seems unlikely.

Perhaps more likely, this is just another case of Nike being very, very good at business in both ownership of creation and retaliation to competitors. As brands continually jab in the courtrooms, nobody has proven bigger or better than the Swoosh, as sales and innovation suggest.

Better yet, if Nike wins, will it lead to the necessity of the next evolution of the shoe upper?

All of this remains to be seen, and whatever side you fall on, Nike still proves first. Thankfully, we as consumers can all enjoy wearing Flyknit Kobes, Primeknit Kanyes and perhaps even Balenciaga Speed Runners as this plays out in the legal system.

Let us know your take on this case on social by mentioning @NiceKicks on Twitter.