This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure policy.

words & interview // Nick DePaula:

Tinker Hatfield is no stranger to innovation.

Over the past three decades, the icon of design not only dreamt up some of the athletic industry’s most storied sneakers from scratch, he’s also pioneered modern chapters for footwear, like the cross training category itself, the notion of exposing Nike’s “Air” cushioning technology, and of course, the Jumpman-donning, bar-setting Air Jordan series.

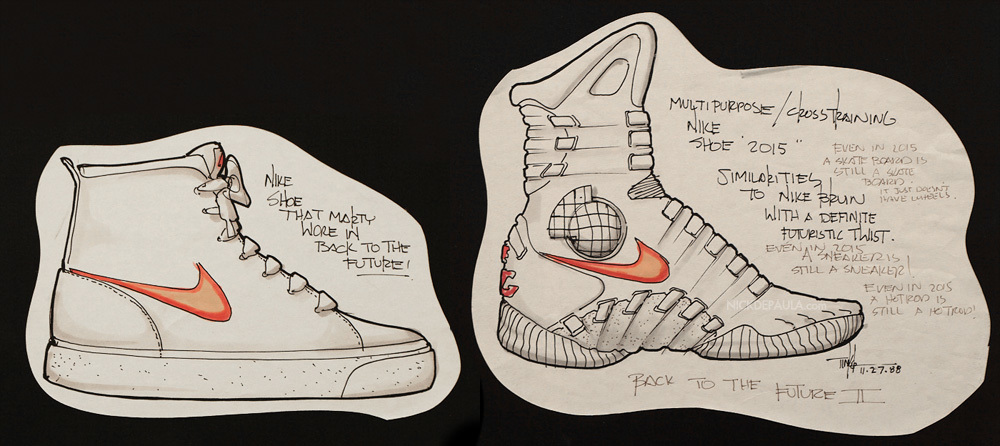

During his early time with the brand, a foundational project came to life — only fictionally — that has always drawn fans to both his work and the mystique around his at-times limitless imagination. It was the Nike Mag from 1989’s Back To The Future II, often simply dubbed the “Marty McFly shoe,” that was so ahead of its time (seriously…by three decades), that by the time the real 2015 came around, Nike actually struggled for years to create it.

Fast forward to 2019, and the brand has yet another new innovation in store. The HyperAdapt BB, a performance-fueled follow-up to the auto-lacing HyperAdapt 1.0 from 2016. Aiming to offer up an on-demand fit for hoops, and bringing to life Hatfield’s vision for adaptive technology, the sneaker syncs up to the unique slopes and contours of the wearer’s foot, all powered by an app system, and playable at the game’s highest level.

Last month, we caught up with Nike’s VP of Design and Special Projects, to hear all about how the newest step in performance design came to be. Read ahead for our in-depth interview with Tinker Hatfield, as he details the brand’s history in auto-lacing, where the concept may be headed over time, and the new HyperAdapt BB, its latest innovation for the future.

Nick DePaula: When you first got the call back in the late 80s and you had your own vision of what the future of footwear could look like, you created the auto-lacing Air Mag. Now that we’re actually here, how close or far off do you think that original concept was?

Tinker Hatfield: I’m gonna go back to that time – back to the future. [laughs] The first meeting, they actually had an idea for a shoe. We were called in to execute their idea, but I didn’t like it. Not liking it is not the best way to describe it. I just didn’t think it was the best way to go about doing a futuristic product with a Swoosh on. [Their idea] was that you could walk up a wall and stand on the ceiling. I was like, ‘Nyeeah – that’s kind of an old gag.’ We’ve seen it in animation and some other movies.

The reality of it was that I felt like if they really wanted to listen to our perspective, that we needed to design something for the future that actually might make sense and still be amazing. That whole notion of power lacing was a concept that I brought in. I storyboarded it and said, ‘Here it is – a lifeless, two lumps of nothingness.’

I knew there was going to be an interaction between Doc and Marty McFly, and the next thing you know, he says, ‘What is this?’ He puts one on and it comes alive. The idea was adaptability from the very beginning. The notion of a shoe that recognizes you and turns on, then adapts itself to you is not very different than what we’re looking at right now. It didn’t really change much.

NDP: When you started to work on re-creating the Mag for 2011, did that also start to serve as the starting point for this project? What was the timeline between the two?

NDP: When you started to work on re-creating the Mag for 2011, did that also start to serve as the starting point for this project? What was the timeline between the two?

TH: It’s a good question when you think about the timeline. We struggled a little bit, because at first we really wanted the original remake of the Back to the Future shoe to power lace. We spent some time trying to make that happen, and it just was fraught with issues. We felt like we were taking a lot of time. The decision was made as a collective decision, and both Mark Parker and myself simply said, ‘You know what, let’s just yank the power lacing part and we’re just going to put a beautiful replica out there.’ Of course, we had to do that funny little ad about why it didn’t power lace. That actually was an idea that came from Bob Zemeckis himself.

NDP: The original director.

TH: He’s great! He said, ‘Well, of course it doesn’t power lace yet, because it’s not 2015 yet. It’s 2011.’ That was a nice out for us. We were still gonna try to make it happen. I don’t think we were really motivated to really get after it until we said, ‘Wait a minute, forget the movie shoe. Let’s take this concept into Nike sports performance.’ I could imagine why a product and a technology like this might help an athlete. It was basically solving an issue to fit properly, automatically. But also, it could loosen when you don’t need it to be so tight.

We’ve all had sore feet from wearing shoes too tight, for too many days. Imagine what we see in the lab or with any professional athlete, male or female, their feet are ruined by the time they’re just even a few years into their professional career. We think as part of a longer-term scenario that that’s going to go away. Shoes will be tight when they need to be, and they’ll be comfortable and loose when they don’t need to be tight.

NDP: As you were nearing the launch of the power-lacing Mag in 2015, how far along were you on this project?

NDP: As you were nearing the launch of the power-lacing Mag in 2015, how far along were you on this project?

TH: We hadn’t even assigned the team for this yet. It wasn’t too long after that, that we had made this decision that we were going to roll up our sleeves and try to help a real athlete perform better in the shoes.

NDP: From a design perspective, Eric [Avar] always talks about the balance of art and science. This shoe is so much more science than any other shoe quite like it. How did you approach the big picture of the design and how far you wanted to push it?

TH: I think that it would’ve been really easy to get a little crazy with the upper and put a bunch more features into this product. But, experience and design education tells me – or whatever expertise I think I have [laughs] – it tells me that you need to pick what your hero is in design. It’s true in art as well. The best designed apparatus, products or whatever, are always ones that are simpler than being overdone. The idea here was that the hero is the fact that it [comes to life] and lights up. It has a character to it. If we were to get a little more crazy, I think it would take away from it a bit. It is the practice of editing.

This [first] one was always that. We always thought about that. One of the original inspirations for [the first HyperAdapt] was a Chuck Taylor. Chuck Taylors are a cool looking shoe. Simple, black upper usually, and a white bottom. Wearable. It does something more than a Chuck Taylor, but that was the nod. Modern day Chuck Taylor – a do-anything-in shoe. Not the best at one thing.

Then, we said that the next move would be to make a more sport-specific, best-in-class performance product. Eric of course took that project on. He’s been working, in particular, with Kobe Bryant over the years, and we learned from working with Kobe that less is more with him. That became a continuing narrative.

NDP: That first HyperAdapt has the puck and piece really exposed. Here, it’s just the two toggle buttons. What was the thinking behind how you wanted to compartmentalize it?

TH: I think it really boils down to, ‘How much plastic do you want exposed?’ And, ‘Is that a good thing or a bad thing for a sport?’ Our collective thought was that we really needed to protect that box more, plus, we didn’t want anyone to slide, slip or in some way get that box in contact with anything to do with the sport itself. We buried it.

The first one, you could hit it on things, and it was fine for a multi-purpose shoe, but for the best players in the world, they shouldn’t have to worry about whether or not something else is going to get in the way of their performance. We buried it, and Eric did a great job, along with a lot of other people, of going through so many iterations and talking to athletes. There’s a tremendous amount of collaborative effort in this product.

NDP: What do you think of the dual branding? What’s it say about Nike to have more fun with the branding?

TH: I think sometimes companies – not just Nike, but other big companies – can take themselves too seriously. This is a little bit of a wink and a nod that we’re really here to help athletes, but also to have some fun. That’s a universal truth for most people. They want to exist and do well, but you should have some fun along the way. That’s just a nod to the fact that basketball is fun.

NDP: This is an interesting project in that there’s not really any restriction on price point. We’ve seen Nike have the Elite Series, but that was at $200 and $250. If this is a fit solution with no restrictions, have you guys ever talked about doing a concept car for different issues, whether that be for cushioning, grip or other elements?

NDP: This is an interesting project in that there’s not really any restriction on price point. We’ve seen Nike have the Elite Series, but that was at $200 and $250. If this is a fit solution with no restrictions, have you guys ever talked about doing a concept car for different issues, whether that be for cushioning, grip or other elements?

TH: There’s not a simple answer, other than to say that we are trying to weigh a lot of issues every time we do these things. Here, we’re trying to make a decision that’s very specific to this sport and to performance. When we move to other sports with this technology, there might be a completely new list of criteria to deal with. We try to handle it differently along the way. There are no rules. This is new territory. We’re kind of all in the same boat, this is all uncharted territory, and we’re not sure what we’re going to do next, to be honest.

You talked about price point too. It’s like phones and other technical innovations that are more expensive when they first come out. The first one was $720, and it’s not as good of a playing shoe as this. The more we keep engineering and re-building these motors, they shrink down, and we can put them into more sizes and fit women better, and maybe kids too. Also, we could retro-fit other shoes with this technology. The more of these you make, the less expensive they get. You could play that out, and at some point, the products are going to be far less expensive, and they’re going to be expected too, by the way. ‘Oh, it doesn’t have power lacing?’

Then, when you get to that point, there has to be something else. Plus, we won’t have to worry about editing the rest of the shoe, cause the story won’t be about that. Here’s the thing too. It’s not just for the NBA, it’s for all levels of players ultimately. And, for people that have issues getting in and out of shoes. You better have a plan to make this technology accessible.

NDP: On the first HyperAdapt, the bands were exposed, and you could see it engage, tighten and come to life on your foot. How early on was the decision made to have a knit shroud over the cables?

NDP: On the first HyperAdapt, the bands were exposed, and you could see it engage, tighten and come to life on your foot. How early on was the decision made to have a knit shroud over the cables?

TH: The first one was a little bit of a nod to the original Back to the Future shoe, where it was so visual and you could see those straps visually suck down. It had to be theatrical for the movie – you had to see it. This one, it still has the theatrics. It was important to connect it, just ever so subtly to the movie. Once the idea is out there, I don’t think we need to worry about connecting it anymore.

This one has tiny little cables, and let’s not worry about going out of our way to expose them so people could see them. People are just going to go, ‘Oh! The shoe totally sucks up around my foot.’ It’s almost like now, it’s a little more fun to be mysterious, whereas the first one was more overt. That might change! [laughs]