This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclosure policy.

Fast cars, fancy watches, and millions missing—the rise and rapid fall of Zadeh Kicks is a cautionary tale about a white-hot business that moves so fast it outpaces both regulators and consumer protection.

To make sense of the story of Zadeh Kicks, we have to first understand a few other things: how a business can operate in a shadow space without direct ties to suppliers of its products; the dangers of non-traditional and high-interest loans; why the sneaker resale business has become the hottest space in men’s fashion; and the platforms that hosted the business and processed the money, and became accomplices in its drastic downfall.

THE BACKSTORY OF ZADEH KICKS

Last month, the world of sneaker resale was shaken by the news that Eugene, Oregon based Zadeh Kicks had requested an Oregon court to dissolve its nine-year-old business, declaring itself insolvent and unable to pay millions of dollars worth of debt.

Days after the filing, zadehkicks.com changed its homepage, directing customers to contact David P. Stapleton, the court-appointed receiver. Within hours, thousands of Zadeh Kicks customers had joined a live Twitter space, looking for answers on how to recover their money, and to share their experiences with Michael Malekzadeh, the company’s owner.

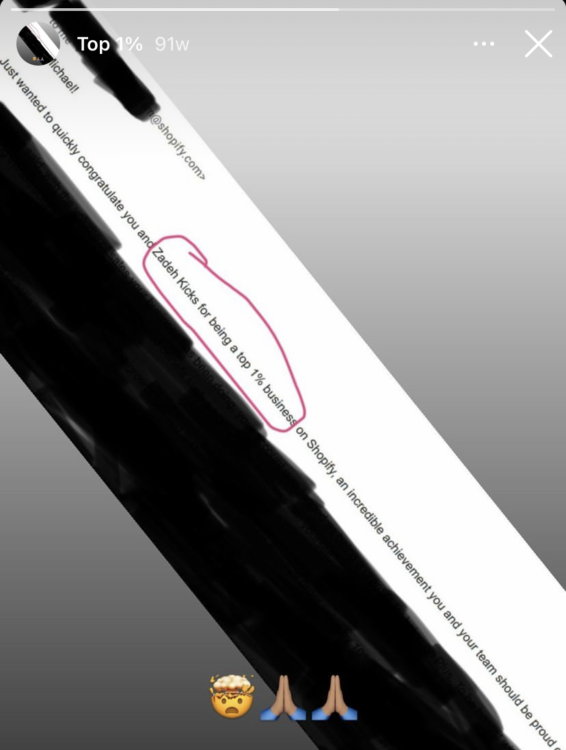

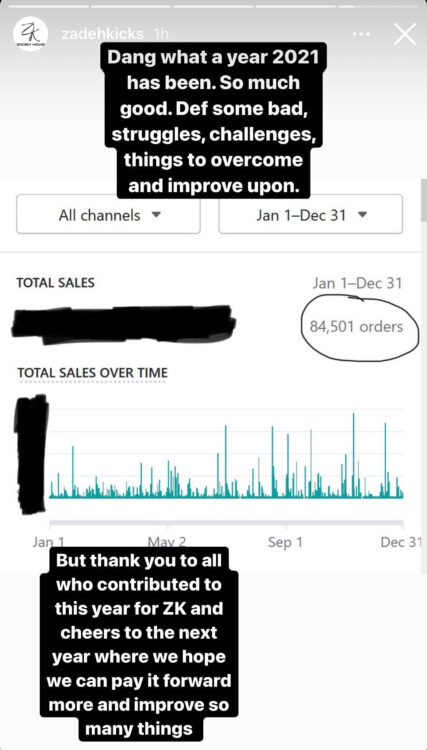

Malekzadeh launched Zadeh Kicks, LLC in 2013 and saw it grow rapidly, climbing to $2M in sales by 2015, $6M in monthly sales in 2017, and eventually ranking in the top 1% of all Shopify Merchants by 2020. In 2021, they recorded over 84,500 sales with estimates of pre-orders to be worth more than $100,000,000.

Zadeh Kicks sold highly sought-after, limited-edition sneakers from the likes of Jordan, Nike, and Yeezy, but had no direct relationship with these brands—or any others. To obtain the shoes—as described on zadehkicks.com before the site was taken offline—Zadeh Kicks would purchase the products from independent retailers and suppliers.

Prior to forming Zadeh Kicks, Michael Malekzadeh purchased older stock from retail stores and sold them on ebay. By developing relationships with the stores he purchased from, Malekzadeh was eventually able to secure newly released products, including retro Jordans, in a manner commonly referred to in the business as a “backdoor” arrangement.

He told me every one of my friends in retail was selling to him, but I never did

Owner of Authorized Nike retailer recalling encounter with Michael Malekzadeh

Nike, like many footwear brands, carefully restricts the products they are able to order and which accounts are authorized to sell those products online. Brick and mortar stores which are prohibited from selling online, though, will often rely on a handful of individuals to handle shoes in leftover sizes, and to clean older products out of the stock room and off the balance sheet. The service that Zadeh provided has been common practice in the sneaker business for years, but has always operated in the shadows of major brands, as this method of offloading older stock to marketplaces like ebay or Amazon is technically a violation of retailer agreements.

A BOOM FOR ZADEH

Zadeh Kicks’ petition for dissolution makes it clear that, beginning in January of 2020, the business experienced “exponential growth” from pre-sales of yet-to-be-released sneakers, but was unable to keep up with that growth, lacking adequate systems to handle the surge in business.

By September of 2020, zadehkicks.com achieved the milestone of ranking in the top 1% of Shopify stores. The @zadehkicks Instagram page has a copy of the email from Shopify pinned despite having deleted 3,432 Instagram posts since February of 2022 and recently made the account private.

The growth continued in 2021 as Zadeh Kicks recorded more than 84,500 orders. A screenshot of this achievement was also posted as a story update on the @zadehkicks Instagram.

A BOOM FOR RESALE SNEAKER BUSINESS

The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting closures of retail stores caused a massive adjustment in the sneaker industry. With little time to plan, brands and retailers had to scramble to engineer new ways to sell their shoes, despite being shuttered in much of the country. Nike, for example, permitted previously unauthorized merchants to start selling online. Large chain stores such as Foot Locker responded by allocating more units to their e-commerce platform as hundreds of malls shut down.

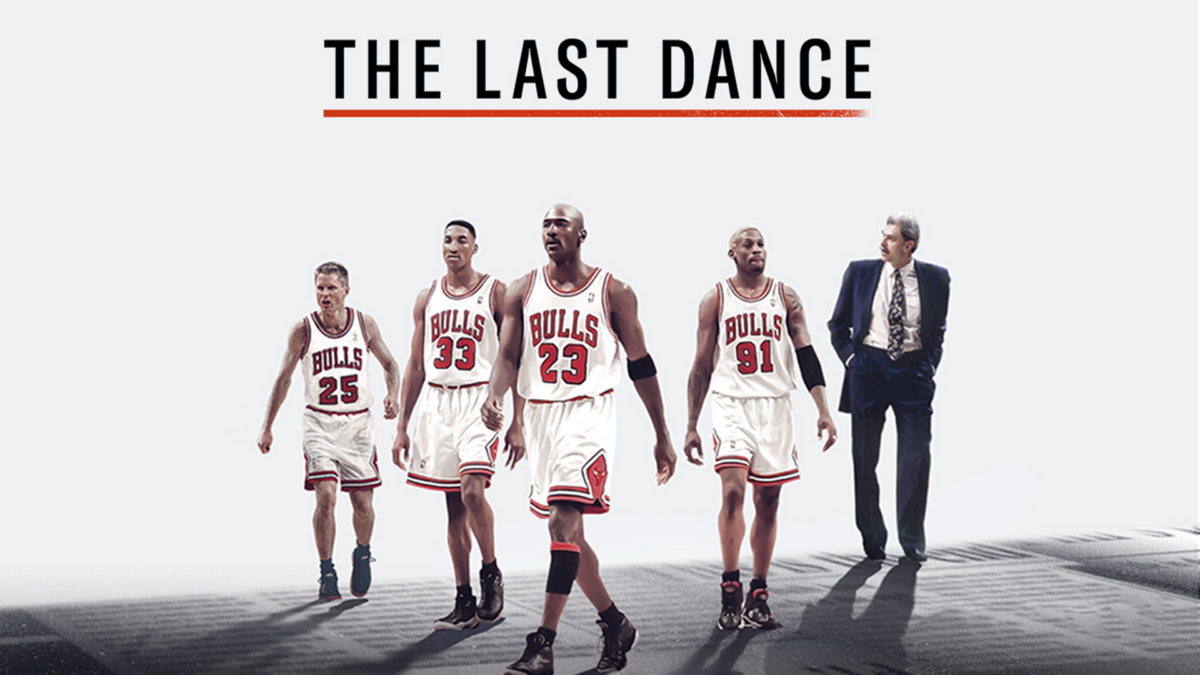

Shortly into the pandemic, the Netflix docuseries The Last Dance aired over the course of five weeks, telling the story of Michael Jordan’s historic final season with the Chicago Bulls. The success of the series was reflected not just in streaming volume, but in an increased demand for retro Air Jordans, driving up prices.

The Air Jordan 1 “Chicago” 2015 Retro, for instance, sold for an average price of $938 in March of 2020; by May, after the last episode of The Last Dance aired, they were selling for an average of $1517.

Another factor pushing up sneaker prices was the federal government’s decision to respond to the pandemic by issuing economic stimulus checks.

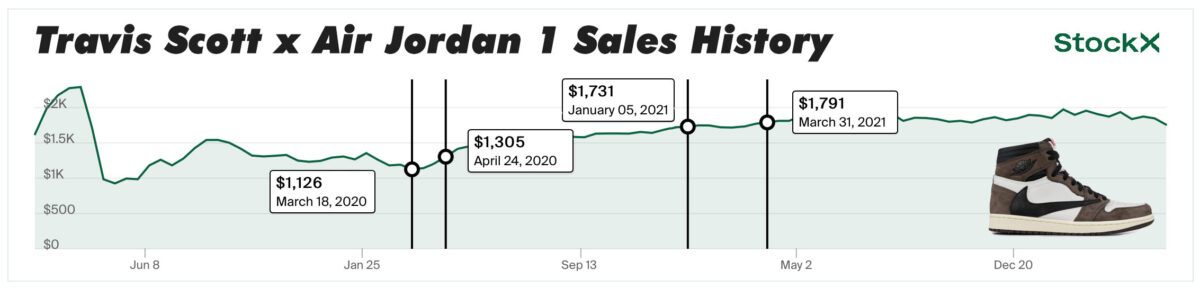

The Travis Scott x Air Jordan 1, released in May of 2019, saw its price peak for the year that summer, and was on a downward trend—until the first stimulus checks started arriving in March of 2020.

“You could watch the Travis Scott Jordan 1 sales jump with each stimulus check,” Ralph Gandara of Sneaker Summit told Nice Kicks in 2021. “All of a sudden, people got $1400 in the mail and the Travis Scotts were right below that, so for a lot of folks they opened an envelope and had a ticket for one of their grails.”

SNEAKERS AS AN INVESTMENT CLASS

On stage in 2015, StockX co-founder and former CEO Josh Luber talked about the market mechanics of sneakers, and alluded to the possibility of a “Stock Market of Things.” StockX, backed by serial entrepreneur Dan Gilbert, launched in February of 2016, offering users the ability to place bids and asks for sneakers, similar to how a stock broker would. It also reported market data on product pages, providing immediate insight into their price history.

In 2019, Cowen Research released a report declaring sneakers to be an “alternative asset class”, projecting the sneaker resale market to reach $30 billion by 2030. In a follow-up report released in 2021, Cowen reported that the sneaker resale market grew 100% in 2020, with the industry passing $2 billion in US sales, and expected 20% year-over-year growth for the rest of the decade. More recently, the group released its third report in the Sneakers as an Investment Class series, maintaining their 2030 projection, and adding that sneaker resale was significantly outperforming the broader e-commerce ecosystem, which had been decelerating into early 2022.

In addition to traditional sneaker resale investment opportunities, there’s been a dramatic rise in interest in one-of-a-kind and game-worn sneakers. Auction houses Soetheby’s, Christies, and Heritage Auctions have hosted sales for shoes worn by Michael Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Allen Iverson, and other NBA Hall of Famers. Christie’s teamed up with sneaker resale store Stadium Goods to curate a collection of eleven pairs of game-worn Michael Jordan shoes, which sold for a total of $931,875.

The most expensive sneaker sale in history took place in April of 2021, when Sotheby’s facilitated the private sale of a Nike Air Yeezy prototype worn by Kanye West during the 2008 Grammy Awards, for $1.8 Million. The purchaser was RARES, a company that enables retail investors to purchase fractional shares of shoes, for as little as $5.

SNEAKER FUTURES

Nike sells shoes to their authorized retailers primarily through two types of transactions:

- at once (also called available-to-ship) orders are products currently in stock

- futures orders booked by the retailer five to six months before release

For both order types, it’s standard practice for retailers to pay for their orders after the product leaves the brand’s warehouse – generally 60 days afterward.

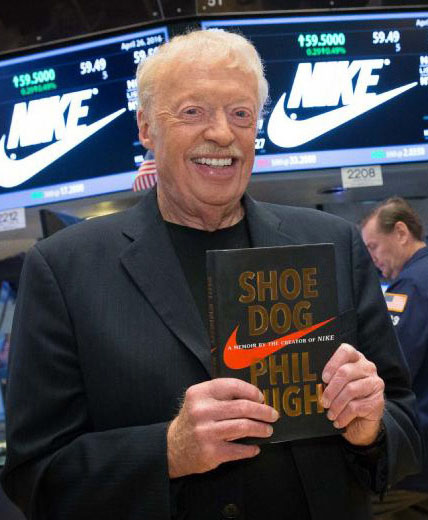

Nike’s co-founder and former CEO Phil Knight discussed in his recently released memoir Shoe Dog about the origin of futures. Nike management essentially made up the concept of future orders as it applies to its business as a cash-generating tool for when times were still lean during their early growth days.

In Zadeh Kicks’ pre-order business model, though, orders were placed and paid for upfront by customers. The window of time between customer prepayment and product delivery varied, typically between three and six months ahead of release.

“In hindsight and looking at things now, when Zadeh was offering pre-orders for shoes, he essentially sold us an options contract or commodity future, but with not exactly the most definitive delivery date set in stone,” a Zadeh Kicks buyer since 2019 stated. “To make it worse, some of the shoes he took orders for he couldn’t have possibly verified that he would have access to because they didn’t exist.”

Some of the shoes he [Michael Malekzadeh] took orders for he couldn’t have possibly verified that he would have access to—they simply didn’t exist.

Bulk pre-order customer of Zadeh Kicks since 2019

Numerous times Zadeh Kicks sold shoes based solely on a Photoshop mockup of a colorway that never came to market.

Since Zadeh Kicks relied on retail stores to supply them through backdoor arrangements, customers never expected to get their shoes ahead of the official release date, but generally received them not too long afterwards. This was generally not seen as a problem for customers who placed bulk pre-orders, as prices tended to start rising shortly after the product was released.

Some pre-orders arrived quickly, though it depended on several factors. “It wasn’t just in the beginning that I received my items quickly or when I had smaller orders, but it was also when my pre-order price that I paid was well above the market price when the shoes came out,” said a regular Zadeh Kicks customer since 2020 who is owed over $25,000.

But then things began to change. “Usually it would take a month to get an order in, but starting in the summer of 2020 some of my orders took two or three months.” a bulk pre-order customer since 2019 who shared with Nice Kicks that he is out more than $3 Million in unfulfilled orders.

“It wasn’t out of the ordinary for the shipments to take a long time to arrive, and almost never did they all come together,” a pre-order customer since 2020 told us. “I placed an order for 200 pairs of Fire Red Air Jordan 4s and I would get shipments of 16-20 pairs at a time. Often a month or two between each shipment.”

Throughout 2020, shipping delays got progressively worse. “By the end of the year [2020], I didn’t mind if Zadeh offered to buy me out of my order rather than waiting for the shoes to come in. There was no telling how long it would take, and I would have preferred to get the money to purchase more pre-orders.”

A pattern to Zadeh’s “buyouts” began to emerge. “Right before the release—usually just a couple days—he would let me know that he had a bulk buyer lined up and really pushed for me to do the deal. At the time, I thought that he made my life easier without having to handle a large shipment of shoes that I needed to find buyers for and if he was able to make a little money off of my order, it would benefit him too.”

Whether or not Malekzadeh actually had a bulk buyer lined up is unknown. In hindsight, buyers we spoke with looked back on these moments as Malekzadeh trying to cover his shortcomings in pre-ordered pairs, and avoid the financial pain of having to purchase on the secondary market to fulfill the orders he wasn’t able to procure from his backdoor suppliers.

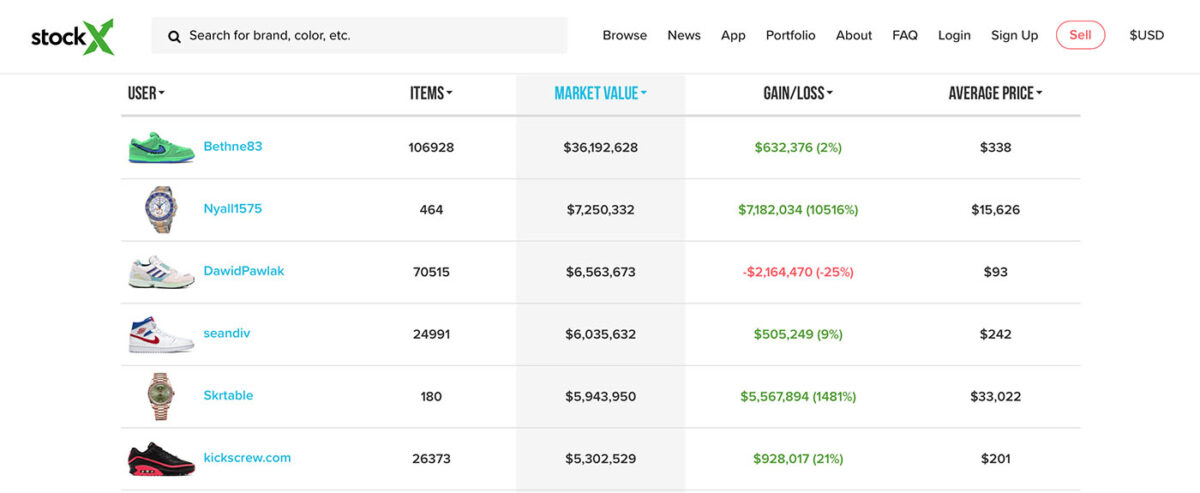

It was not a secret that Zadeh Kicks had an active relationship with StockX as a customer. A former employee of StockX reached out to Nice Kicks to confirm rumors that Zadeh Kicks was the marketplace’s biggest buyer, registered under the same username (Bethne83) used on Instagram by Bethany Mockerman, Malekzadeh’s girlfriend. Mockerman also described herself on LinkedIn, at various times, as a Financial Coordinator, Finance Manager, and CFO at Zadeh Kicks.

For a few years, StockX publicly displayed the “portfolios” of StockX users if they granted permission. The portfolio would add any inventory they chose to upload, but it also automatically added items purchased through the StockX platform.

There was nothing particularly wrong with Zadeh Kicks using StockX to purchase shoes, but the large volume of purchases on the secondary market indicated how many pre-orders Zadeh Kicks was filling this way, rather than by purchasing from retailers or other suppliers.

THE BANK OF ZADEH

Zadeh’s offer to buy out customers’ orders had existed for several years, but starting in late 2020, an alternative method of transfer became available: gift cards. Rather than sending money by bank wire to repeat pre-order customers, the gift cards allowed for money to stay within the Zadeh Kicks bank account. For customers, using gift cards to place additional orders was easier than transferring cash.

“Though the cards came quickly, it was a pain getting a long list of these cards,” explained a Zadeh Kicks customer since 2019. “The cards would be added to your account, but since they were capped at $9,999, not only would Zadeh have to manually create a bunch of the cards, we would have to apply them individually with each order.” Shopify’s Service Terms cap the value of gift cards at $9,999.

Zadeh was not a fan of refunds of any kind either. Not only were buyers repeatedly threatened with being banned and blocked if they asked for a refund, but the policy page on the Zadeh Kicks website listed numerous scenarios where store credit would be issued instead of refunds…in the form of a gift card. Shopify policy, however, states that gift cards may not be used in place of refunds to compensate consumers for unshipped merchandise.

The gift card system helped Zadeh Kicks keep money within their system, and effectively delayed the point at which they had to fulfill shoe orders or provide payouts. “Eventually, Zadeh created incentives to take buy-outs in gift cards instead of money wire,” a customer since 2018 shared with us. “In one instance, I was offered $200 per pair if I did a money wire or $210 by gift card.”

But just like the shoes, the money transfers weren’t always fast. “He would be upfront about it, and explain that he needed a few weeks to make the wire transfer. Getting a little more than the wire and having it immediately meant it just made more sense to take the store credit to place more pre-orders.”

In April of 2021, Zadeh Kicks started using rise.ai, a third-party Shopify plugin, that offered gift cards with no limits. Rather than using gift cards that were part of the native Shopify system, with a $9,999 limit, bulk buyers could now have unlimited value gift cards that functioned more like funded accounts.

Because of the new cards that could be loaded with any amount, one could wire transfer hard funds to Zadeh Kicks and get a loaded credit in their account to spend without the credit card fees or inconvenience of handling 20-30 cards.

“Between us [other Zadeh buyers], we would joke that we had a bank account balance and a ‘Z buck’ balance with a collection of huge gift cards sometimes valued at more than $1 Million.”

There was a change of rules and no longer could we buy in-stock items with store credits—only pre-orders. Then after a while, we couldn’t just use store credits to book new pre-orders—we had to add money too.

But eventually, Zadeh Kicks put limitations on how “Z bucks” could be spent. “I couldn’t remember when it was exactly, but there was a change of rules, and no longer could we buy in-stock items with store credits—only pre-orders. Then after a while, we couldn’t just use store credits to book new pre-orders—we had to add money too.”

A CYCLE OF LOANS AND DEBT

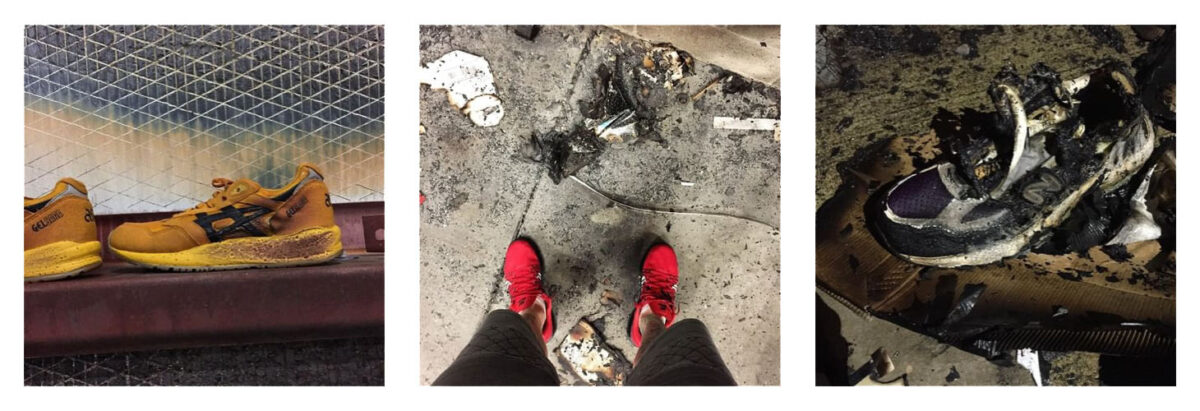

From the beginning, Zadeh Kicks faced an uphill battle with loans and debt, just as many new businesses do. In October of 2014, only a year after it formed, a fire occurred in the Zadeh Kicks warehouse located at 710 Commercial Street in Eugene, Oregon. According to Michael Malekzadeh’s recounting of the events to Sole Collector in 2015, the warehouse held more than $400,000 worth of merchandise at the time of the fire, which was allegedly started by a candle knocked over by a stray cat.

Malekzadeh found himself having to wait several months for his insurer Liberty Mutual to pay his claim. “Honestly, I owed people money for product that I got,” he said, “and I was getting kind of nervous on what I was going to do.”

Malekzadeh also spoke to forbes.com about debts and loans for an article titled #SmallBizHowTo: How To Get Financing For Your Startup Or Small Business, You Asked, We Answered. In the piece, it was revealed that Malekzadeh had invested $30,000 of his own money into the business he started in 2009, under the name Zadeh Concepts.

He also took out Merchant Cash Advances, which provide capital upfront to businesses, which are then repaid, plus fees, using a percentage of the business’s future sales. This type of loan is infamous for causing debt traps, where merchants borrow to repay a prior loan, creating a repeating cycle that puts them deeper and deeper in the hole. According to Malekzadeh’s recollection, that first loan grew to become ten or twelve from multiple lenders, with payment terms ranging from three to nine months. “The worst one I did, I’m pretty sure, was $75,000 at $110,000 payback. As long as I’m flipping my product frequently, I’ll still make money, but I have to work my butt off to pay all that interest,” he told Forbes.

By October 2015, Zadeh Kicks had secured an inventory line of credit up to $240,000 at an interest rate of 18.99%, and a $70,000 term loan for 12 months at an APR of 22%—rates closer to those of consumer credit cards—to get away from the Merchant Cash Advance cycle. But despite these obtaining lines of credit, it wasn’t long before Zadeh found himself going back to more Merchant Cash Advances.

In 2017, Zadeh started working with John Ponte of Ponte Investments, a provider of merchant case advances based in Warwick, Rhode Island. Ponte stated that Zadeh was a good client initially. “He checked out—in the [loan] business we have a database of businesses that have inaccuracies with their bank statements and Zadeh was never a concern for us.” Ponte was also reassured by the volume of Zadeh’s sales. “He was doing between $5-6 million a month which was quite an impressive business,” he shared in an interview with Nice Kicks.

But in 2019, the relationship between Zadeh and Ponte took a different turn. “The initial red flag was that he was selling shoes to my son, and there was an issue with delivery. I don’t think he knew that my son ordered shoes from him, but there was an order for $10,000 or $12,000 and he was giving my son the runaround. No way would I imagine that this would be a foreshadow for what would happen years later.”

“The final straw came when Michael was disrespectful to my staff,” said Ponte. “Initially things were okay, but he started to get pretty arrogant, and all of a sudden Michael wanted to dictate the terms we were going to accept and, well, we didn’t accept them or his business.”

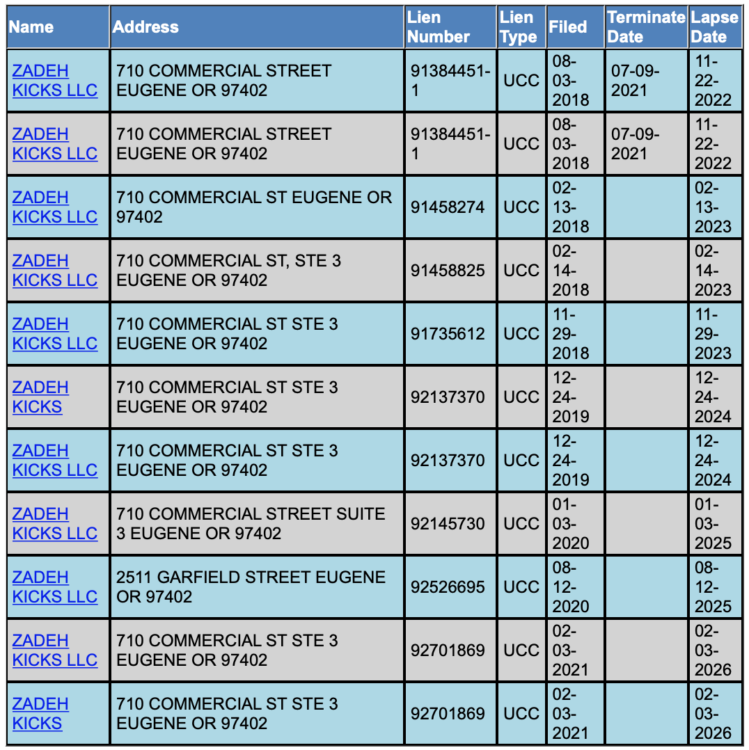

According to a UCC record search from the Oregon Secretary of State, Zadeh obtained additional loans before and after his relationship with Ponte ended. The first loans registered with the Oregon Secretary of State were filed in February of 2018 and at this current time, there are seven active loans for Zadeh Kicks. The loan amounts and payment terms are not publicly available, but Nice Kicks obtained documents of loans that Zadeh Kicks secured in 2019 with Platinum Asset Funding, LLC, another business loan provider based in New York.

Besides their voluntary dissolution, there are no known legal proceedings that Zadeh Kicks or its owner Michael Malekzadeh are a party to, but documents detailing some of their loans were attached to an unrelated lawsuit in New York County between Chatham Capital Management and Platinum Asset Funding.

According to these documents, Zadeh Kicks obtained a loan from Platinum Asset Funding in April of 2019 for $1.2 Million, with a payback amount of $1.656 Million, to be paid in 52 weekly payments of $31,846.15. Before repaying the loan with Platinum Asset Funding, Zadeh Kicks borrowed an additional $900,000 with a payback of $1,242,000, in 52 weekly payments of $23,884.62. The effective APR of both loans is 38%.

In March 2020, Zadeh Kicks’ weekly payments of $55,730.77 for the two loans were reduced to $6,000 in what appears to be an adjustment that coincides with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to documents filed with the New York County Clerk as of September 15, 2021, Zadeh Kicks owed $753,615.32 on the second loan.

While it’s not completely clear what occurred in April of 2022, it appears that Zadeh Kicks’ run was soon coming to an end. The website disappeared without any warning for a couple of days building angst amongst those waiting on orders and unanswered emails. But problems appeared to have been bigger than technical when Michael Malekzadeh called Tim Waldbridge–the owner of 503 Motors.

“Michael said something about having a large chargeback and needing money to cover what was owed. He had a car at the shop that he mentioned was just sold to Chicago and be on the lookout for a shipper.”

All at once in a single transaction, Michael Malekzadeh sold multiple vehicles in his collection to Chicago Motor Cars. While it is not certain what Michael was paid for the vehicles, four of the cars he used to own are for sale for a total of $3,049,200.

After nine years of business, on April 29, 2022, Zadeh Kicks stopped accepting payments.

THE CASUALTIES OF ZADEH KICKS

Zadeh Kicks’ dissolution left hundreds—perhaps thousands—of sneaker collectors and resellers financially devastated. In researching this story, Nice Kicks spoke directly to 17 customers of Zadeh Kicks, with undelivered orders ranging from $3100 to more than $3 million. Due to potentially pending litigation, some agreed to speak on the record, under the condition that their names would not be published.

A twenty-three-year-old customer of Zadeh Kicks started mowing lawns at nine years of age, refereeing youth basketball games as a teen, and bought and sold shoes while going to college. Professionally he works as an account executive at a Salt Lake City-based tech firm but has been repeatedly disappointed in attempts to afford a down payment in a competitive housing market swarming with out-of-state cash buyers. So he decided to take every dollar he saved and put it to work, by doing what had always given him the best return for his buck: placing a pre-order for sneakers with Zadeh Kicks.

A thirty-one-year-old customer of Zadeh Kicks from upstate New York remembers wanting the “Chicago” Air Jordan 1 since missing the release in 2015 and placed his first order with Zadeh Kicks for the shoes in 2019 along with a few other pairs shortly after that he sold to local sneaker resale shops. After seeing repeated success over a couple of years the contractor and property investor joined with his friend to invest more with pre-orders of sneakers with Zadeh Kicks, selling a combined three houses to come up with $751,000 in undelivered goods.

A twenty-four-year-old customer of Zadeh Kicks from Southern California had three successful experiences of placing pre-orders when a few of his friends wanted to pool their money together with his to place an order for more than $1 million. Despite having earlier success working with Zadeh, the order placed in 2021 for Cool Grey Air Jordan 11s has left them without shoes and without answers.

These collectors, along with thousands of others, put enormous faith in Zadeh Kicks, a platform that they saw as innovative and unique, with an associated community of sneakerheads who shared their passion. What they didn’t see, for the most part, was the enormous risk they were taking on.

THE BLAME

It’s easy to lay the blame for this catastrophe entirely on the shoulders of Michael Malekzadeh. He was, after all, more or less the sole driving force behind Zadeh Kicks, and displayed plenty of behaviors often associated with financial predators.

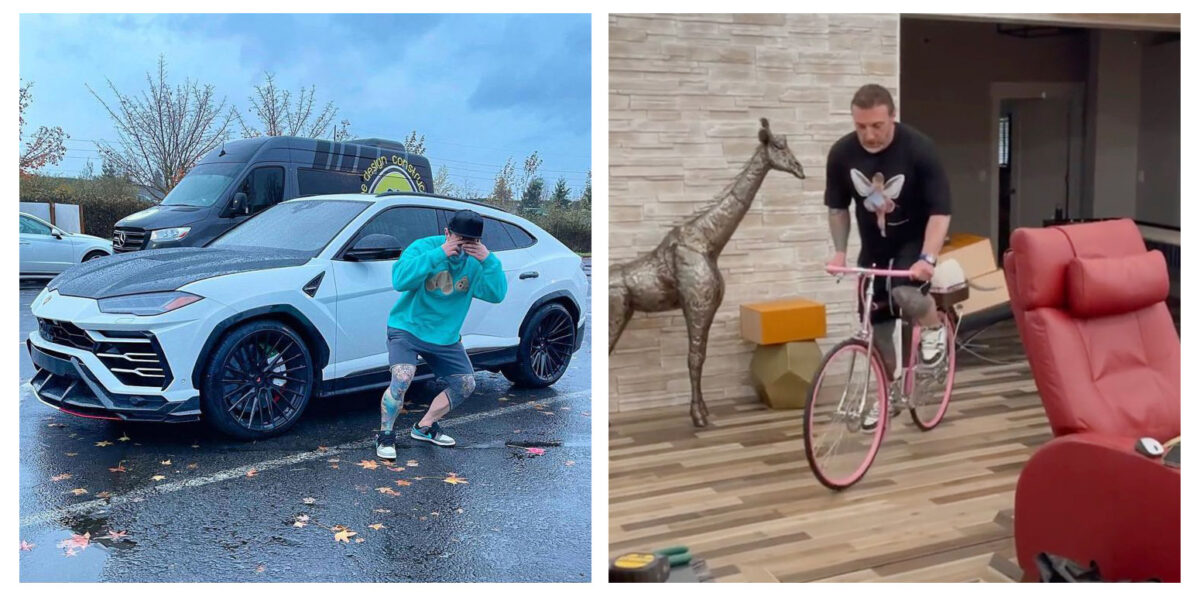

His penchant for fast, expensive cars was always on full display, with photos frequently popping up on social media of Malekzadeh in front of his Lamborghini Aventador SVJ 63, McLaren 765LT, Rolls Royce Cullinan, or another of his 10+ high-end rides. His online communication alternated between bombastic and elusive, highlighting huge sales numbers while offering endless excuses for shipment and payment delays, changing policies with no explanation, and making vague promises of future improvements. For collectors who engaged heavily in the Zadeh Kicks marketplace, he was also an intimidating presence, openly threatening to ban and block anyone seeking a refund.

But it’s not as if these behaviors are unique, or even all that unusual. The world is full of self-serving, smooth-talking players looking for an angle, but most are constrained by regulations and oversight, especially where large sums of money are involved. If you think of other secondary markets where a lot of money changes hands—cars, art, property, etc.—they’re all tightly regulated, with clear procedures for how to conduct transactions and file complaints, and enforcement entities with real teeth.

The secondary consumer goods market is different. Buying and selling hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of sneaker pre-orders is conducted, basically, the same way as buying a single pair for $80 from a friend: with no consumer protections, no reporting requirements, and no financial reserves. This would be like buying a house with no requirement for inspections, no title insurance, and no escrow.

Consumer goods lack this kind of oversight because, up until recently, it wasn’t necessary. Buying a product on the secondary market usually meant purchasing a dress at a consignment shop, or ordering a used projector on ebay, so there was a limit on how much money was involved, and often a third party that set up its own policies to protect buyers and sellers.

The secondary sneaker market, though, has become a huge business, with bulk orders reaching millions of dollars, and—especially in the case of Zadeh Kicks—a thriving pre-order market, with such long lead times and high volumes that it essentially became an unregulated futures market.

Zadeh Kicks’ pre-orders are far from the first and won’t be the last that cause financial harm to consumers. The State of California sued Kanye West’s Yeezy brand under consumer protection laws on the books regarding shipping times. Might it be time that similar laws are drafted regarding pre-order sales too?

The two largest sneaker resale platforms, GOAT and StockX have a combined market valuation of $7.5 Billion following their most recent rounds of fundraising last year and with the continued hints at a StockX IPO on the (actual) stock market, it’s long overdue for policymakers to have a deeper look at how current our consumer protection laws are that govern the space.

Michael Malekzadeh could be seen to some as a con artist, but he was also could be viewed as a sneaker enthusiast who got in over his head and realized too late that there was no lifeboat to grab onto.

Some of this slack was ultimately taken up by credit card companies, who did an admirable job of helping customers recoup their losses. Numerous individuals who had conversations with representatives from American Express, interviewed for this story, were told that Zadeh Kicks’ dissolution resulted in one of the largest chargeback volumes they’d ever processed for a single vendor. The catch, however, is that chargeback protections are usually limited to 180 days from the date of purchase—longer than the lead times on many hot sneaker pre-orders.

Reports from customers regarding their experiences with PayPal haven’t been as positive. While initially it appeared that PayPal was making customer service a priority for customers of Zadeh Kicks, news broke last night, June 14th, that numerous people who filed claims on PayPal received notice that their accounts had been frozen until further notice.

What is unclear at this moment is to what extent the platforms Shopify–the platform Malekzadeh used for the business to interface with the public, PayPal–a payment intermediary was used to accept millions of dollars in payments, and Chase–the bank that Zadeh Kicks used for company banking, missed in their reviews and audits of a business of this size using their platforms.

What measures should be in place that ensure store credit is backed up by a certain level of liquidity for the merchant? As we write and rewrite laws about payment new payment methods for a changing digital landscape, how can we have better policies that make the “good as cash” store credit exactly as described?

If there’s a lesson to take away from all this, it’s that unless someone starts regulating the secondary consumer goods market, Zadeh Kicks is just the beginning. As with so many digitally-enabled services, the buying and selling of futures in consumer goods has expanded faster than laws and policies can effectively regulate it. A platform like Zadeh Kicks wouldn’t even have been possible in the early 2000s, but now it’s almost trivially easy to set up using existing tools and platforms.

Sneakers are at the forefront of a new kind of investment, and it has a powerful cautionary tale in Zadeh Kicks. The question is, will other investment communities learn from it?

Michael Malekzadeh is represented by David Angeli and the Angeli Law Group. In the course of our investigation, we spoke with his representation and received this official statement below.

Out of respect for the FBI’s ongoing investigation, it would not be appropriate for Michael Malekzadeh to comment at this time on the specifics of what is a very complicated situation. However, he is 100 percent committed to doing everything he can to minimize the fallout on anyone who may have been negatively impacted.

As previously reported, according to an email sent out from the receiver, he is working with the federal government in a criminal investigation regarding Zadeh Kicks.

Anyone who believes they are a victim can call the FBI at 1-800-CALL-FBI.

Michael Malekzadeh has not been charged with any crime at this time.

The FBI has posted a form for seeking victim information at fbi.gov. If you have done business with Zadeh Kicks and are owed either money or shoes you can provide your information to the authorities at the link above.

July 29, 2022: Zadeh Kicks Founder Michael Malekzadeh and CFO Bethany Mockerman were indicted for wire fraud, conspiracy to commit bank fraud, and money laundering. (justice.gov)

August 3, 2022: Michael Malekzadeh and Bethany Mockerman plead not guilty to charges of wire fraud, conspiracy to commit bank fraud, and money laundering.

December 16, 2022: Zadeh Kicks inventory is being liquidated on ebay.

Revision history:

June 15, 2022: initial publication

June 15, 2022: typo correction

June 19, 2022: typeface format change

July 29, 2022: Zadeh Kicks’ Malekzadeh + Mockerman Indicted for Wire Fraud, Conspiracy to Commit Bank Fraud, and Money Laundering

August 3, 2022: Zadeh Kicks Owner + CFO Plead Not Guilty to Criminal Charges

August 19, 2022: added link to FBI.gov form Seeking Victim Information

December 16, 2022: Zadeh Kicks inventory is being liquidated by the Receiver on ebay

April 16, 2024: Updated dead links to archived pages